From Wounded Knee to Custer - National Parks Trip Part 4

From a simple, unkempt roadside memorial to 71,000 acres of the best-kept public lands in the country

We broke camp at Badlands to discover fresh bison tracks circling the tent. Penny had sounded off a whispery “buff” during the night as if she needed to tell me something big was just outside, but she didn’t want to sound off a full-fledged bark. Perhaps she was trying to tell me a buffalo was clomping around not five feet from the rain fly stakes, but English isn’t her first language.

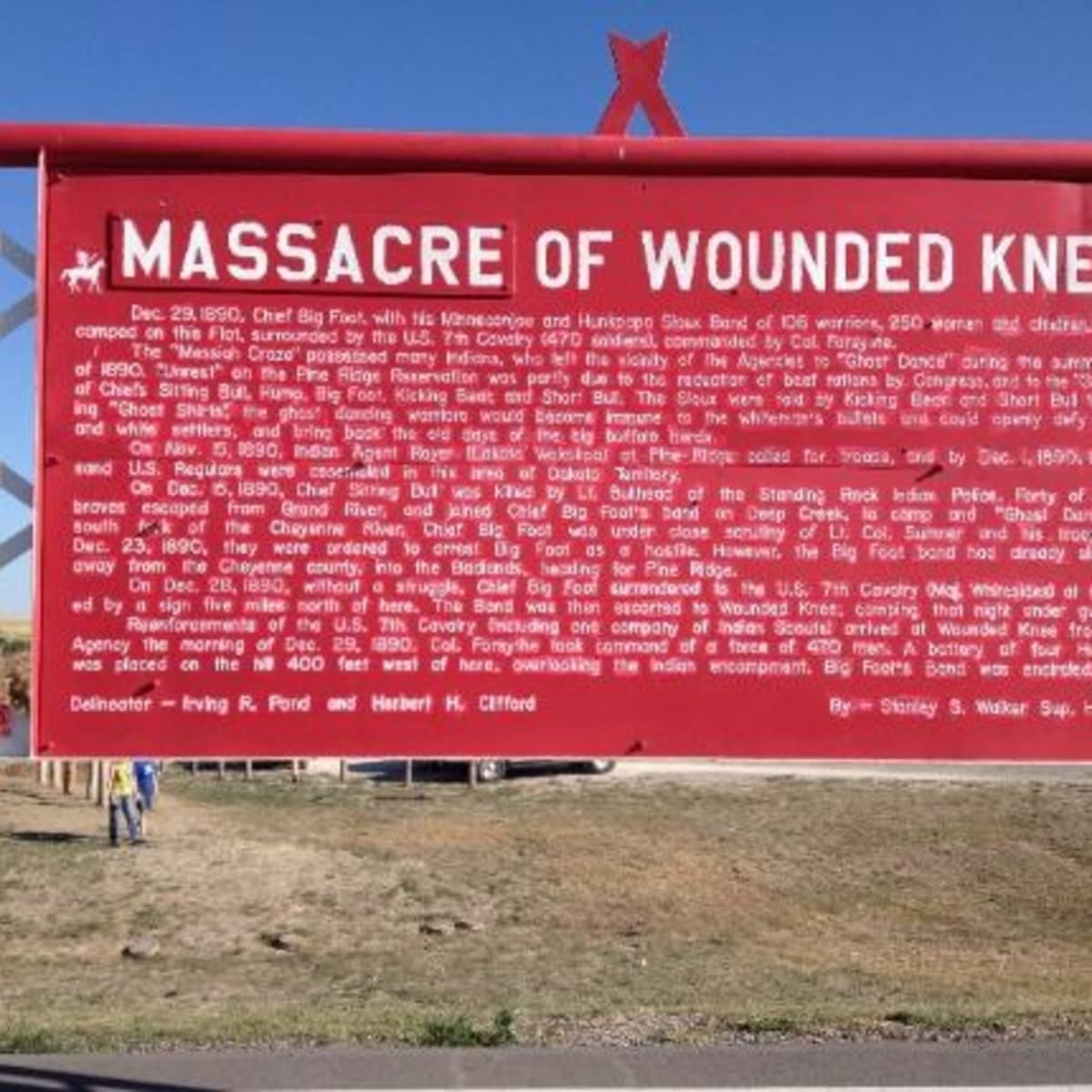

Before continuing West, we drove South to visit the site of the Wounded Knee Massacre. Although my Middle School history books referred to it as a “battle,” in actuality, what went down at Wounded Knee on December 29, 1890, was the deadliest mass shooting in American history.

After the surrender of Big Foot, soldiers of the 7th Cavalry were disarming the Lakota warriors. During the process, a shot was fired, although accounts differ as to which side shot first.

After that, all hell broke loose.

The Army used four rapid-fire Hotchkiss artillery guns to spray the Lakota encampment. Some of the warriors attempted to fight back, but most had already surrendered their weapons.

Even after the Lakota attempted to flee, the soldiers chased them down to brutally murder them. Bodies were strewn in the snow, stretching for two miles.

By the time it was over, 250 people of the Lakota had been killed, and 51 were wounded (4 men and 47 women and children, some of whom died later); some estimates placed the number of dead as high as 300.

The Army also lost 25 soldiers. Thirty-nine more were wounded.

Nineteen soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor for their deeds at Wounded Knee.

After some of the Native American bodies froze on the ground for several days, a military-led burial party dumped them into a mass grave.

I don’t know what I expected to find at the site, but it wasn’t a painted plywood sign on the side of the road. We pulled into the gravel drive to read the sign. A woman asked us if we wanted to buy some of her jewelry.

The bowl of green grass behind the sign is the site of the massacre.

On a hill across the street is the site of the mass Lakota grave.

It is marked by a simple granite marker engraved with the names of the Lakota tribal leaders who lost their lives there. The marker was commissioned in the early 1900s by Joseph Horncloud, who had been a teenager during the massacre where both of his parents and two brothers were killed.

There are far larger and more elaborate markers in the Episcopal cemetery in Tarboro, NC. They are possibly for people of less character but certainly more means.

It feels wrong.

Forty Acres along Wounded Knee Creek are on the National Register of Historic Places. The roadside placard and the memorial are run-down and unkempt. She was almost forgotten.

From Wounded Knee, we headed for Custer State Park. Encompassing 71,000 acres in the Black Hills, Custer State Park is named after Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer.

Custer died in the Battle of Little Bighorn, where he and the 7th Cavalry were grossly outnumbered by Lakota warriors. As many as 3,000 Native Americans attacked Custer and the 200 men in his battalion. Within an hour, Custer and all of his soldiers were dead.

My middle school history test failed to mention that Custer also led an expedition in 1874 that discovered gold in the Black Hills of the Dakota Territory, the same ground that is now Custer State Park.

Following the discovery of gold in the Black Hills mountain range, prospectors flooded into the hunting grounds and “unceded lands” of the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Dakota, and Lakota tribes living there, violating the terms of the Treaty of Fort Laramie, which set aside these areas as the Great Sioux Reservation in 1868.

Some people believe that the 7th Cavalry opened fire on unarmed Loakota men, women, and children as revenge for what happened to their regiment at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

The next leg of my westward journey had me traveling from that rickety painted roadside sign at the gravel pull-off where a young woman was hawking jewelry to 71,000 acres of some of the country's most beautiful and well-kept public lands.

I don’t know what the moral of this story is. I’m still trying to figure it out.

Maybe don’t trust the government. Or at least don’t let them take your guns.

That might be a good place to start.